This model was the key to unleashing my son's potential

Research in the high-performance psychology of the flow state

First off, happy holidays. I hope each and every one of you has a joyous holiday season and gets some time to relax, recharge, and honor what is sacred in your life. I’m grateful to all the readers here, whether you have been here from the beginning (hi, love) or this is this first time reading. All of you make this worth doing, and worth continuing to do better.

Now on to this week’s letter.

Let’s start with some basic premises.

Our model of education doesn’t look like school.

We’re trying to create unique opportunities for our children. Laszlo Polgar calls it genius education. Henrik Karlson calls it Childhoods of Exceptional People. Malcom Gladwell calls them Outliers. Whatever you choose to call it, that’s what we’re educating towards.

To quote John Taylor Gatto: “genius is an exceedingly common human quality, probably natural to most of us.” Every child has the capacity for genius, but we need to raise them to cultivate it.

We’ve forgotten how to raise geniuses. Our educational model isn’t interested in raising geniuses. But our society runs on new breakthroughs, new businesses. Progress. For those reasons, and for the happiness and potential of our children, it’s worth rediscovering how to raise them.

The day to day of creating these kinds of outcomes is as unique for every child as their personal genius.

I’ve been trying to raise my children to cultivate their personal genius. It started as I wanted to help my son catch up. Then my son wanted to build an airplane. Now I’m obsessed with figuring out what my son is capable of…and helping him do the same.

As obsessed as I am, I still get it wrong a lot of the time.

For nine days last week my wife and I went to Costa Rica. Nine days where the kids were at home with my in-laws while we were not. Nine days where I didn’t know how the plan was going or how good his work was that day or whether he needed something different because the work was too easy or too hard. For the first time since I took over his education, for nine whole days, I placed my son’s learning into someone else’s hands. Then I came home.

Returning, I was ready to go. He was… something else.

The first morning, I sat down at the table. He slouched over a foot away, rather than his normal spot practically on top of me. I opened the book; without hesitating he asked how long we had to work. His right leg started bouncing up and down before I could answer. We read for five minutes and he asked if he could take a break. A few minutes later he got up to get a snack. Later it was milk. He dropped his pencil once, then twice, and then a third time. Again he asked how long we had to work for.

30 minutes later we opened our practice book and picked a few problems to try. The first question asked him to identify all the factor pairs of 48. He wrote a 4 that took up half the page, followed by an 8 and a 12 so small that the graphite was barely visible. Opposite the page like an opposing army on the field was a 6. I asked him if there were any other factors. In response, he drew two eyes and teeth on his 6 and armed his 4 with a knight’s broadsword. “Can I show A my work?”

In two hours we finished a page and a half of problems. Before I left, we would have done five pages in under an hour. In history we read 11 pages about ancient Judea and Israel. I asked him a question about the ancient prophets. Samuel had just anointed Saul the first king of Israel. My son laughed when Samuel poured the holy oil on Saul’s head. When I asked him whether he thought the prophets had been good leaders, his brown eyes looked through me.

“What’s a prophet?” he asked.

I’ve long been convinced that every child has the capacity for genius. So what gives? Why does my child’s genius seem to be fidgeting, dropping pencils, and avoiding work?

It’s not the first time we’ve stalled. I used to get so frustrated when he wasn’t living up to his potential. I’d take it personally, as an indictment of my abilities. At my lowest, I told my wife I wanted to quit. We seriously considered sending him back to public school.

But then I learned how learning actually works. Even though we still stall out, I still spend lots of time managing his fidgets and his distractions and his ADHD, I know what to expect. And I know how to get back to that state of learning.

If we’re really going to understand learning, we need to look at the flow state.

The state of flow is a psychological state of peak experience. Athletes call it “being in the zone” and talk about the feeling of being absolutely confident in themselves. It’s like being on a hot streak of your own making. It’s like you’re playing 4D chess with a bunch of people who only know how to play checkers.

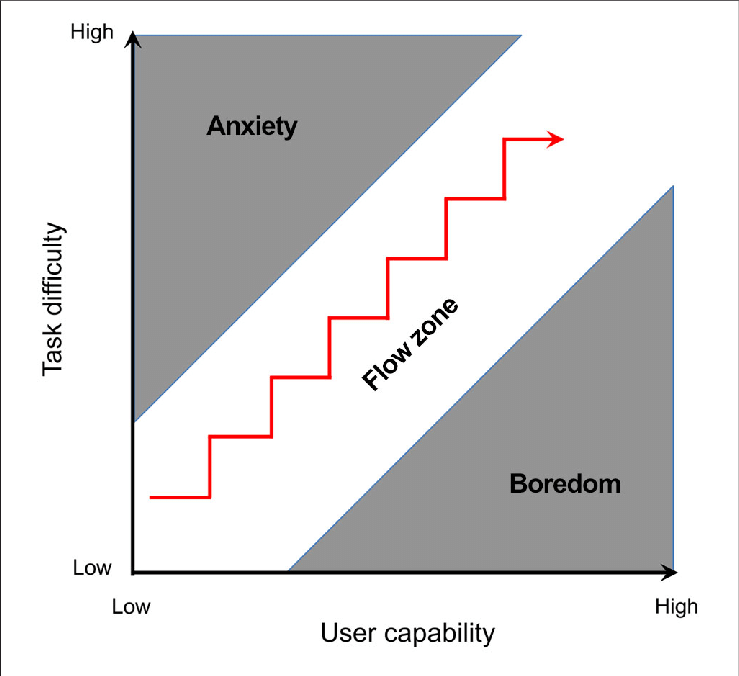

To quote Flow Research Collective: “Flow state is a highly focused and immersive mental state in which an individual's skill level matches the challenge of the task, resulting in reduced self-awareness, altered time perception, and heightened positive emotions.”

In other words, when you’re in flow, you lose all track of time, feel great about what you’re doing, get so absorbed in the moment that you forget about yourself, and grow at an exponential rate.

True learning, the kind of learning that empowers us to bring our genius to the world at hand, is an act of flow.

We generally know what gets people into flow

Getting into the flow state is hard enough as an individual. But as home educators, we need to manage the flow state for our children. How the hell do we pull that off?

Researchers have identified tips for achieving flow. Tips like finding your flow triggers, setting clear goals, and balancing challenge and skill all help you get into the flow state. Let’s look at a few of them as it relates to our kids.

Flow Triggers are those conditions or activities that set the stage for getting into flow. These are unique to each person, which means you’re likely going to have to try a few. For us, they sometimes change day by day. Sometimes having classical music on in the background helps, but sometimes it’s too distracting. Often times we need to work into flow by starting with some easier tasks before we go on to more challenging ones.

To get into flow, our kids need to believe that they can be successful and learn the material. It would be great if my son was always internally motivated and believed he was capable. But oftentimes a little reinforcement from Dad will do the trick. When we’re setting out to learn, I’ll regularly tell him how good he is at math, or at learning language. I’ll give him concrete examples of things he does really well. I’ll try to make him proud.

We can also help our kids’ internal motivation by knowing what makes them feel good about their work. We’d all love learning to be this purely altruistic activity, but for my kids that’s not always true. Sometimes the thing that gets my boy feeling good about himself is that he’s better at it than other kids his age. Other times it’s someone he admires or some career he thinks would be really cool. When I started listening to him without worrying about his moral compass (his moral compass is fine), I was able to help him get into a flow state more often with better results.

Flow, by definition, is the point where challenge and skill meet. If a problem is too challenging, he gets anxious. If it’s too easy and he already has the skills, he gets bored. It needs to be just challenging enough, at that sweet spot between his ability and the challenge level. He has to work.

When we’re learning I need to manage the difficulty he faces. We regularly work on hard problems, the kinds of problems they don’t assign in school. Last week we proved the Sieve of Eratosthenes. We learned about electron orbitals in science class and tried to use that knowledge to understand why water molecules have the shape they do. But we work on them together, and if it seems too difficult I supply lots of hints. I ask lots of questions that guide him to figuring out how to solve the problem.

I’ve learned over time to manage the challenge he’s experiencing, not the difficulty of the problem I’m asking.

I’d add one more that’s not in the research, but I’ve found true for my boy. Flo is a result of momentum.

My son rarely learns smoothly after a break. Learning, as a skill, is a muscle, and when it’s not exercised it atrophies. It gets a little bit harder to get into that flow state. The gears turn a little bit slower. But after we get back in the groove of things, he does much better. Hell, I do much better. It’s easier to get into flow when we’ve been closer to flow recently.

Two days later, we returned to math. More factors. This time we were looking at perfect squares, trying to get at the fact that they’re the only numbers with an odd number of factors. [footnote: perfect squares are numbers that are the square of a smaller number. 4, 9, 16, 25, 36, 49, etc. They have an odd number of factors because one of their factors is multiplied by itself.] He wasn’t getting the concept, so we decided to explore some numbers. We wrote out the first q1 perfect squares and he factored them.

Then his head bowed over his hand and the paper. His pencil started scribbling furiously and his eyes filled with hard intensity. He let out a long, drawn out exhale and I waited for the next inhale. I kept waiting as lead covered the white paper with arrows and numbers and stray marks.

I stared with growing worry at my child. I half expected to see the words mene, mene, tekel, parsin written out on the paper. I could have told you how King Belshazar felt at that very moment. I leaned to the left to try and get a peak under his arm, but he gave me no room.

His pencil moved with increasing fury, and my curiosity swirled with increasing passion. I needed to know what had captured my boy, but he was lost in the moment. His mind, his hands, his breath: they had all taken a back seat to some idea, and I wasn’t a part of whatever was going on.

Finally, he breathed again. Desperately, like he’d finally reached the water’s surface.

“I found a pattern.” he excitedly showed me.

He pointed to 4, then 9, then 16. “To get from one perfect square to the next, you add an amount that increases by two every time.” We had learned that chapters ago, but he was so excited I just watched.

“And then every other perfect square has exactly three factors, where the even perfect squares have more than three. And I think there’s a pattern for the number of factors in 16, 36, 64, and 100, but I haven’t found it yet.”

I smiled in awe. My boy was back.

But getting your own child into flow is all about trial and error

Understanding flow helped me understand how to cultivate my son’s unique genius. It’s one of many lessons learned along the way.

But how do you create the same for your child?

Practice.

You need to jump in and try things. You need to get to know your child. And you need to learn from others.

Every piece of advice, every biography, every scientific research paper should give you an idea. Then you bring it home and try it out. And try it out again, and figure out what else you can try.

That’s what I’m doing here. I’m taking all of that information and making it actionable and usable.

Latham

The education we’re creating and the airplane we’re building are made possible by you, generous readers. If you want to support a better education for one very special little boy and the chance to change education one child at a time, there are a few ways you can help:

Consider upgrading to a paid subscription. Every dollar supports this education.

Share this post with your people. Forward it, tag someone, share it on Social Media, or print if and give it to someone you know. Every person can help.

If you’re not ready to become a paid subscriber, you can always make a one time donation here at Buy Me A Coffee. Each donation buys one small part of our airplane.

Both my son and I are grateful for your support.

That on top of all this you are taking the time to stop and articulate the insights, your own learning about teaching, wins and the struggles is so generous and impressive Latham. I am not teaching my child this way, but I have an inner child that is subject to many of these challenges and your reminders about flow state and how it can be supported was very useful to me. Thank you.

I was also very impressed when I initially read Henrik Karlsson’s and Erik Hoel’s articles about aristocratic tutoring. I started my Substack https://mindbicycles.substack.com/ as a way to explore the same topics. I also find the counterarguments by Tomas Pueyo:

https://unchartedterritories.tomaspueyo.com/p/where-geniuses-hide-today and Steve Hsu: https://youtu.be/qqsdD4pxdWw?t=1568 very compelling: there’s no stagnation, we are still making plenty of geniuses but there’s no more individual genius; they are part of research teams and companies and they mostly come from prestigious schools and universities. Maybe there’s some truth in both sides of the argument.