Before we really begin, let’s talk about what this is

I think the way we understand learning hasn’t kept up with the world. Most of us know that schools were created in an industrial age, designed to create industrial workers. What we expect from our schools has changed — they need to keep up with the knowledge era of work at a minimum — but I’m not so sure our understanding of learning has caught up.

When I took over my son’s education, I knew the old ways of school weren’t working. I didn’t want to create an industrial worker or a knowledge worker. Sure, I was looking to develop creativity, critical thinking, and problem solving skills that school doesn’t teach. But more than that, I wanted to help my son preserve his curiosity, develop agency, and cultivate his personality so that he could live an abundant life. I’m pretty sure that’s the point of learning. But our understand of learning still starts with memorizing facts and doing exercises. It’s still stuck in an industrial age.

I think the way we understand learning needs to catch up.

And even though I’ve felt it, I realized I hadn’t talked about it. Which is a loss, because I’m going to guess you feel it too.

I don’t know what the answer is yet. Mostly I have a lot of questions, and even more frustrations. But I’m going to find it. I’m committed to figuring it out. Nothing short of my children are at stake. And I’m hoping you all will help me. Hoping we can figure it out together. I’m going to be working through it by exploring stories, asking hard questions, and talking to people smarter than me. With your help.

So that’s what this is.

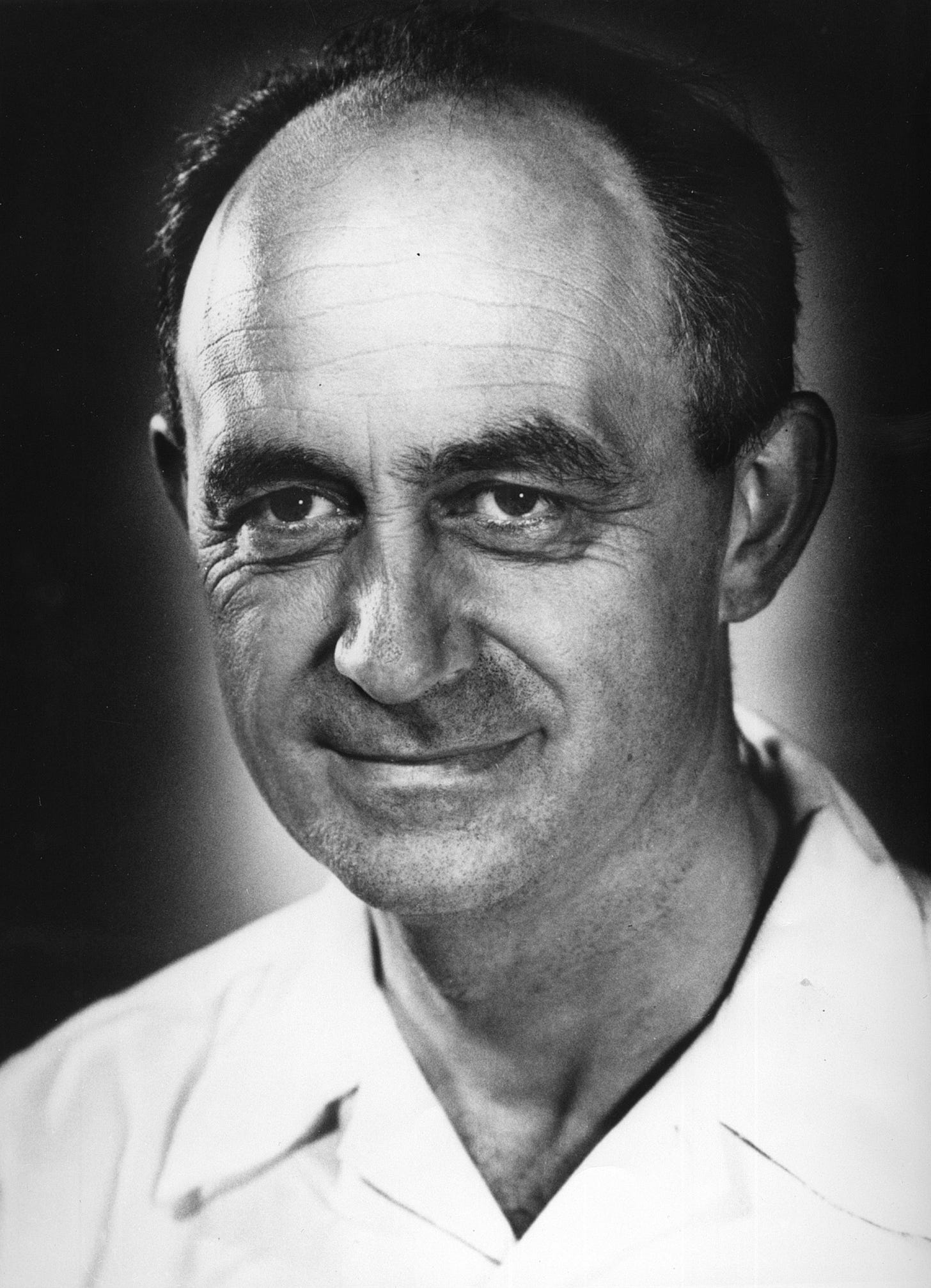

Enrico Fermi gave one of the coolest lessons in real understanding I’ve ever heard

In 1945, Enrico Fermi was one of hundreds of scientists working on the Manhattan Project. During the Trinity Test, which was the first detonation of a nuclear device, Fermi decided he wanted a rough estimate of the amount of energy released by the blast before any diagnostics data came in.

“About 40 seconds after the explosion the air blast reached me. I tried to estimate its strength by dropping pieces of paper before, during, and after the passage of the blast wave. The papers during the shock wave fell about 2 1/2 meters… estimated to correspond to 10 kilotons of TNT.” — Enrico Fermi

This simple, back of the envelope calculation is an example of a technique called a Fermi Estimation. It’s often used by some of the smartest minds in science, technology, and business to approach a rough estimate answer, saving time and pointing towards the right direction.

I think about that moment with Enrico Fermi regularly. The man ripped up shreds of paper, didn’t bother measuring any of them and probably had no idea how much they weighed, dropped them onto the floor, took a wild ass guess as to how far they fell, and used that to estimate the size of the world’s first nuclear blast. And he got amazingly close. The actual yield? 18 kilotons.

Damn that’s cool

We were taught learning is memorizing meets manipulating equations. True learning should be about manipulating the world around us.

It wasn’t until I was a student Test Pilot that I learned about Fermi Estimation. I was sitting in my cubicle, the sweltering heat causing the pages of my flight manual to curl at the edges, trying to calculate the precise onset rate I would need to pull the stick back in order to get the right acceleration to hit the test point without exceeding any limits. It was a nasty problem, and I was attacking it with every formula I’d learned in school, when an instructor walked past me and started laughing.

“Hey Turner, I can figure out in 30 seconds if you’re wasting your time.”

I was not in the mood.

“Look at the max G you can pull on the stick. No matter how fast you pull, you’ll never exceed that limit. So stop wasting your time and go fly.”

Really? That calculation I had just spent 45 minutes on. That calculation that had made sweat drip through my flight suit and my brain feel like silly putty squeezed into one of those plastic eggs. You’re just going to abuse me like that?

You could easily assume he just knew more about the plane. And he did, but there was more to it. You see, he didn’t just know more information, he knew how to use the information he had in the real world.

In the world of school, we’re taught to find the precise right answer. There is some model, and that model, with the right inputs, will always lead to the right answer. And if we can just get the right information and practice the right calculations — we’ll be right. And that’s the point of the game.

But in his world, the point wasn’t to be right. It was to safely take the best information he had and make a timely decision. He didn’t look for the right calculation, he used the best mental model he had to figure out what mattered. And then he ran that through some assumptions. It was the intellectual version of taking a massive risk.

That kind of risk taking and problem solving isn’t taught in school. In fact, it’s punished in school.

See the problem?

So…we aren’t the only ones who see it. Right?

I see some people that are starting to notice it. They see that there is a problem. And that’s huge! They’re even talking about what our new goals could be.

Recognizing the problem and reimagining the goal is great. Yes, we need the next generation to be able to solve problems. Yes, we need them to embrace their creativity. But as much as that, we need real world ideas of how to create those outcomes. We need to figure out how to make our child see the world in all its messy, beautiful, crazy wonder. And that’s the practice.

The practice is the day to day. It’s when you’re sitting with your child and trying to help them understand a concept and you’re racking your brain to help them see it. It’s when the fear sets in, the little voice that says “I don’t know how to do this,” but you keep trying anyways. It’s when you’re so excited to try some new idea with your child because you’re sure they will fall in love with it. It’s when you’re so far beyond what a teacher or any textbook advises that you’re making it up as you go and hoping your kid will at least recognize how much you love them. Isn’t that building the plane while flying it? (I will only apologize this once for the bad pun)

That practice is why I agreed to let my son build a plane. But it’s also why I’m not stopping there. I want to figure out how to bring math, science, stories, language, everything into those lessons. I want to design a world for him centered on his interest in airplanes. But I want the practice to expand beyond what I can imagine.

And yet we don’t talk about the practice. Nobody has written the book about how to integrate every part of your child’s day, week, month around a single idea so that they understand what it means to be immersed in it. To really KNOW it.

Because that’s what I see when I think of Fermi dropping his torn up shreds of paper. The man knew nuclear physics so well that he could estimate the energy on the fly. He didn’t just know the names of the particles or the type of reaction, he knew how the world would change when they harnessed the power of the atom.

That’s knowledge.

When you become obsessed with how to ignite that, you start to really notice how much education sucks. What do you do then?

There’s an $8B textbook industry trying to sell you the latest science on how your child should learn math or reading or history. None of those textbooks even begin to broach true deep understanding. They start with a worldview that believes enough facts in isolation will eventually make an education. They move our children through those facts as if everything has been solved and we just need to get them into the child’s head. We intuitively know that’s not true. But we use them anyways. Why?

I suspect it’s because we don’t know what else to do.

On the opposite side of the spectrum, there’s the unschooling movement. Child directed learning. They’ve seen that the way we’ve been taught to learn doesn’t work. It extinguishes the spark of learning more than it enlightens. And they’re right, but I think they’ve thrown the baby out with the bathwater.

My child certainly isn’t directed to learn math on his own. That’s not the way his interests work, at least not initially. But I am convinced he needs to know mathematical thinking in order to understand how the world really works. I want him to learn Greek and Latin because those are the preconditions to participating in 3,000 years of western culture. Not too many children will self guide into that knowledge.

Fermi may have followed his own interests that led him to nuclear physics. But along the way we had help. he had mentors and guides who showed him what he was capable of. He had a solid foundation of knowledge that he could pull to connect the dots.

And that’s my concern with simply following only my child’s interests. There is a lot I know about the world that he doesn’t yet understand.

Both extremes of the spectrum have removed the most important element. ME.

How do we encourage our child’s interests? How do we help them see what they can’t yet see? How do we integrate everything we want them to know into one rich tapestry of a worldview filled with wonder and knowledge? That how, that’s the practice.

You’re out there trying to figure it out, just like I am. We’re both out there exploring, without a guide. Maybe without a model of how this could work. Do you feel confident ditching the book because you understand how to build that world for your child without it? I don’t. Do you see yourself as the kind of person who is willing to step away from what your peers think, from what the experts say, to try and find a better way of doing things? That’s really scary.

But just as Fermi used everything he knew in his gut to understand the world, your understanding of the world ought to matter. You should build off it. You should update it. Because it’s your child, not some experts.

That practice will ultimately evolve our understanding of learning. It’s what will create the next 1,000 geniuses — I’m convinced of that. Not people who learn the tricks Fermi shared. But people, like Enrico Fermi, who so deeply understand the world that they can devise a new technique on the fly. People who can connect the dots in ways none of us could. Students who go beyond what they are taught and become adults who create what we could never teach.

Your practice — their learning. That’s why we took on this crazy ass endeavor in the first place. That’s what keeps us coming back. Because we can change things.

So it’s time we start asking those questions.

You know I'm a fan of your project, but I think there are several nuances missing here. The first is that there is no singular "education." No matter how many attempts have been made to standardize K-12, kids get very different experiences depending on the wealth of their school districts, the size of their communities, and even just individual decisions that teachers make. It's kind of like Ron Bieber's meaningless statement that Berkeley should be able to explain why it costs $X more than Cal Davis, even though there is wide variability in quality within both schools.

I wonder if there is a "both and" option here rather than an either/or. I know you have personal reasons for your choice. But my three kids all love public school, as I did. They have the benefit of having lived in two college towns with a very buoyant peer group. Maybe they could be progressing faster in some areas with customized learning, but they already do some of that with podcasts and independent reading, not to mention casual conversations with me (a PhD). I am aware that my attitude would be very different if we lived in my hometown, where resources are considerably diminished and the peer group largely doesn't aspire to go to college. And special needs complicate the picture, too.

But do we know how Fermi achieved his mastery of physics? Presumably there was a lot of rote learning involved in the early stages, before he could improvise as he did. I'm mindful of how these repetitive forms of learning are baked into even ancient traditions, like martial arts, where the student often performs tasks that seem mundane and meaningless until their teacher's method one day comes plain. See "The Taste of Banzo's Sword," for instance, or the cheesier (but still true to form) version in "The Karate Kid."

https://ashidakim.com/zenkoans/91thetasteofbanzossword.html

I don't mean to be difficult, but part of learning is point/counterpoint. Curious about your thoughts.

I love the call out here to embrace and encourage intellectual risks in others. It seems like what we call "instinct" in many cases is actually a highly intelligent form of sub-calculation we do in the basement of our thinking that has real genius to it if we don't demand a 20-hour powerpoint from our own brain in order to prove that the information is trustworthy. And it seems like kids already have a relationship to and trust in that. If we can only stop from breeding it out of them!